Reading Letter from Birmingham Jail in Trump’s America

What the monumental letter can teach us as we face the second Trump administration

It’s become a yearly habit to read Martin Luther King Jr.'s Letter From Birmingham Jail at some point, often around this time of year. On Sunday, I decided to listen to it during a long drive.

It’s a cruel coincidence, but perhaps fitting for our times, that this year we observed King’s holiday on the first day of Trump's second presidency. Yet, it also allows us to reflect on these two consequential forces of American politics and how King’s words explain and offer a strategy for the incoming whirlwind that will be the second phase of the Trump era.

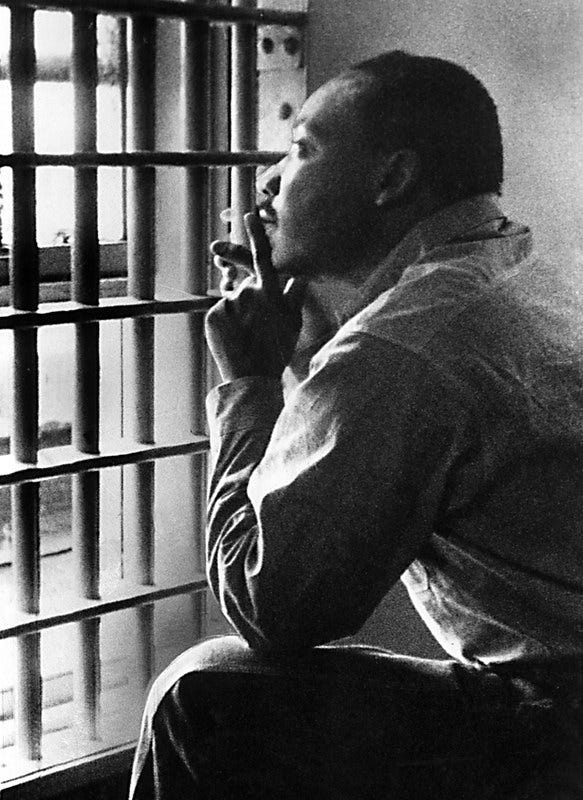

In April 1963, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and the Southern Christian Leadership Council began protests in Birmingham, Alabama, to demand the end of municipal segregation ordinances. Martin Luther King Jr., the leader of the SCLC, was arrested on Good Friday for violating a court injunction that prohibited the protests. He and other demonstrators were arrested and taken to Birmingham city jail.

Placed in solitary confinement, King read an editorial from eight white Birmingham clergy criticizing the SCLC for its tactics, arguing that while they agreed with the SCLC’s cause, they didn’t want street protests and instead preferred for the matter to be settled by the courts and through “negotiations among local leaders.”

King, who had always planned to be arrested to bring attention to their Birmingham campaign, spent his days in jail penning a response to the letter. Drafted in the margins of newspapers passed along to Reverend Wyatt Walker, who edited and pieced together the essay, King's “Letter from Birmingham Jail” became a monumental piece of American protest literature.

The letter is a call to action. It tells those who disagree with King’s methods, those who want more moderate and drawn-out strategies, and those who sanctify law over justice that they have become obstacles to progress. Though he was thankful that the white moderates who had criticized him shared his goal, he saw their disagreement with the movement’s direct nonviolent action methods and calls to wait for a more opportune time as detrimental to true justice.

The whole paragraph where he lays this out is worth quoting here:

“First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: ‘I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action’; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man's freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a ‘more convenient season.’ Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

As Trump kicks off his second administration with a slew of executive orders threatening trans people, migrants, the poor and the environment, all while testing the limits of our government by trying to corrupt how we interpret the 14th Amendment, it’s hard to blame moderates for this situation. And while we could argue that the election was lost because of moderate strategies that failed to raise enthusiasm for a languishing Democratic party, moderates’ true threat still lies in the future.

We saw how moderates watered down the 2024 presidential platform to appease and try to win over the more xenophobic and conservative factions of America. Now, the threat is that they will run the same playbook with Trump. In 2016, he won without the popular vote. This time, he won it. Democrats, in an attempt to match what they think is the public’s sentiment, could give in too much to Trump and once again morph their party’s platform and policy ideals into effectively nothing. It’s a weak strategy that is already playing out.

Recently, 12 Democratic senators broke rank with their party to vote in favor of the Laken Riley Act, a racist bill that would force the government to imprison indefinitely undocumented immigrants who are accused, not convicted, of a crime. The bill was never meant to become law. It was an election-season messaging bill to argue that Democrats were not taking action on immigration. But after the election, some Democratic senators feared being seen as weak on immigration and voted for it. Now, it’s just a House vote away from becoming Trump’s first legislative victory. Some Democrats might argue that the policy is popular, but that is beside the point. It’s unjust, disastrous for undocumented immigrants and further advances the narrative that migrants are dangerous and must have their rights curtailed for the safety of Americans. It also shows how cowardly we can expect some Democrats to act in pursuit of not looking like cowards.

We can’t base our strategy for the next four years on fear based on conservative narratives of what Americans want. Just as King notes the difference between just and unjust laws, we need to understand the difference between good policies and merely popular policies. As we enter the second Trump term and news of immigration raids, the possible end of birthright citizenship and anti-trans legislation grows, we should remember that even if the majority of American voters voted for a man driven by xenophobia and hate of all that’s different and even if most Americans want harsher policies, it doesn’t make it morally just. We must strive to have our electoral outcomes reflect justice, not let electoral outcomes dictate what justice is.

The Civil Rights Movement’s methods were not widely supported in their time, nor was King. In 1961, the majority of Americans said that non-violent direct actions such as sit-ins at segregated lunch counters and “Freedom Buses” hurt the movement to end segregation in the South. By 1965, most Americans supported an equal rights voting law, though an even larger majority wanted only moderate enforcement of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. By 1966, most Americans had an unfavorable view of King. Today, he is viewed favorably by nearly all Americans.

We have a responsibility to continue pushing for progress despite far-right forces and the calls for moderation and patience from those who claim to be on our side. There’ll be tension, but as King said in his letter, we shouldn’t fear tension, for constructive tension is necessary for growth. Those who ask for true progress may be called extremists, just as King was. But we must then ask, as he did, “What kind of extremists we will be? Will we be extremists for hatred or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice?”

I don’t know whether the arc of history bends towards justice. I don’t know if we'll move directly towards a better future by losing the moderating forces slowing progress. And I don’t know how King turned his solitude in jail into such an enduring diagnosis of this country’s struggle and a clear call to action, but I find comfort and motivation in his words. I find comfort in knowing that a little over two years after he wrote the letter, the Civil Rights Act of 1965 was passed thanks to the movement's steadfastness in their strategy despite opposition from conservatives, public opinion and moderates.